Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Steve Swell: Appreciating the Avant Garde Today

Steve Swell: Appreciating the Avant Garde Today

[This is the third of an All About Jazz series of interviews and articles on "The Many Faces of Jazz Today: Critical Dialogues" in which we explore the current state of jazz around the world with musicians, journalists, and entrepreneurs who give us their own unique perspectives. In the first interview of the series, saxophonist Bobby Zankel spoke about his efforts to maintain his creativity and independence in an increasingly "homogenized" consumer-based environment. The second interview with public relations expert Terri Hinte , elaborated on how musicians promote their wares and what this means in terms of how the jazz industry evolved over the past half century. In the current interview, trombonist Steve Swell gives his reflections on jazz outside the mainstream and the explosion of creativity and diversity that has taken place.]

Steve Swell is a New York based trombonist who for forty years has pursued music at the frontier, variously called avant-garde, the new thing, free jazz, the "outside," music that goes beyond conventionality, is sometimes controversial, and often challenges the listening process. From his early exposures to trombonists Roswell Rudd and Grachan Moncur III, as well as innovators like Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, and David Murray, he has joined others in America and Europe who compose and play outside standard expectations. Such music is dismissed by some critics and lauded by others. Regardless of opinion, it has influenced all of jazz, regardless of genre. In this interview, Swell reflects on the place of such music in the ever-expanding jazz scene of the New Millennium. He also shares his ideas on how listeners and musicians can expand their horizons to appreciate music that initially seems foreign or disturbing.

All About Jazz: Steve, when did you start out in the music business?

Steve Swell: I'd say around 1975.

AAJ: So, since then, how do you see that jazz as a vocation has changed in those years since you started out?

The Current Jazz Scene: Thriving or Declining?

SS: First of all, there are a lot more musicians who are interested in improvising. I would say that in a lot of different styles and genres, improvising is almost mandatory as part of the technique that people need to have. Even classical players need to improvise on a lot of the new music that's being composed. Also, there's much more competition for performances and tours for the many excellent musicians who are out there!

AAJ: It sounds like you think the changes have been very positive.

SS: It's positive in the sense that many more people are coming to the music and taking an interest in it.

AAJ: Some would say that the audiences for jazz have declined significantly.

SS: I don't know what measures they're using for that. I just know, when I play at clubs in New York City or elsewhere, we get pretty good crowds. Just last night, I played at a venue in Kingston, New York, in a small club in a small town in the Catskill Mountains, and we filled up the place. There's an audience for all varieties of jazz around the world today. As for the big venues and big money, that depends on what situation you find yourself in.

AAJ: That's an interesting observation, that the accessibility of jazz, live and recorded, has vastly increased due to globalization, small town venues, availability in multiple formats, a click away now.

SS: I think that's true. To some extent, it depends on the kind of music we're talking about. I'm playing with bands that do original music -we're not playing standards, and many times we're improvising whole concerts without any pre-determined music whatsoever. I've found that there's a core group of people who absolutely love that kind of music throughout the world.

AAJ: That seems to go contrary to the pessimism that many in the music business have about the opportunities for musicians to perform and get their message out. They say audiences and venues have declined.

SS: Well, they've been saying jazz is dead for a very long time.

AAJ: Would you agree that it's harder to be a jazz musician today than when you came up in the 1970s?

SS: No, it's always been hard no matter when, how, or where you came up. It's a lifelong commitment, you have to work at it every day, and with the amount of work you put into practicing, working in a band, finding gigs, at the end of the day, the amount you receive from all of that, you're not really well-compensated for all the work you put into this art form.

AAJ: Do you have any thoughts about what could be done to improve the financial situation for musicians?

SS: Well, at a recent meeting of Chamber Music America, someone proposed a change in grants from institutions or foundations, where they give money to a group rather than an individual. In that way, more musicians can extend themselves more easily, and it will take some of the pressure off them.

AAJ: Have you ever worked with a grant yourself?

SS: Many times. And I've worked with others who pursued grants. When Anthony Braxton won his MacArthur grant, around 1995, he used a lot of that money to present his first opera at John Jay College, and all the musicians involved received some of that grant money through Anthony.

AAJ: What do you think foundations should be aware of in giving grants, so they can be a really positive force in jazz?

SS: One suggestion would be for them to make it more of a level playing field. Of course, it's important that they give grants to musicians who've been out there and struggled for a long time, like Roscoe Mitchell or Wadada Leo Smith, both of whom recently won sizeable grants. That's well-deserved. But I think there needs to be ways that musicians in general can get access to enough money to live on and take some of the pressure off.

AAJ: Do you feel that there is a good environment for the younger musicians today?

SS: Absolutely! For one thing, it's a lot easier for them to check out all the music that's around, They can just go on the internet and find an amazing array of stuff to listen to. I myself listen to many more musicians now than when I was coming up. Back then, I was limited to reading Downbeat, listening to the radio, and buying some LPs. Today, there's so much more at your fingertips. But that can be a double-edged sword. Too much of it numbs people. But for whatever interests you and lights that fire under you, you have an unlimited "library" of recorded music available.

AAJ: Who are a few of the musicians that you yourself have listened to recently?

SS: When I listen to music, I'm always trying to pick up new things, so that affects what I choose. Wadada Leo Smith and Henry Threadgill really grab me in that way. I'm listening to how they pace their performances, their sound, how they formulate their compositions. I love listening to Roscoe Mitchell. For me, it's about how they're organizing their music and their concerts.

Jazz Outside the Mainstream

AAJ: Let's talk now about where you are with a lot of your work, namely, jazz that's outside the mainstream. Terms like avant-garde, third stream jazz, "the new thing," free jazz, experimental jazz, crossover music, world music have been used, but what it all adds up to is that what we call jazz has expanded incredibly over the years. The question is how we can begin to make some sense out of all the different forms of music out there, so that when we're listening to something new and unfamiliar, we can put it in context. For example, it took some time for me to grasp what Cecil Taylor was trying to do, as distinct from what Ornette Coleman aiming at. I know you became interested in various new approaches even when you were just starting out. So maybe you can give us a handle as to how to make sense out of the very diverse forms of music that we have at our disposal today.

SS: First of all, I like that you're trying to help people to relate to such music with more sensitivity and appreciation. Let's take some examples of how they could do that. First, they should realize with regard to so-called "free jazz" that Ornette Coleman came up playing the blues. Cecil Taylor came up playing classical music. So there's a continuum between so-called mainstream jazz and classical music that informs a lot of free improvising and innovative forms of jazz.

It's not like they decided to do something that came out of nowhere. It didn't come out of nowhere; it came out of a tradition. You can hear the blues in Ornette Coleman. I'm surprised when I find out that some people today can't even hear something that Ornette did fifty years ago. Whether you can put a name on his music, to me it's just the name of the musician, It's Ornette's music, it's Cecil Taylor's music. It's David Murray's music. If you go and listen to David Murray's records, you get an idea of what that music is, and you say, "Oh, that's David Murray."

When young musicians are learning, they really get into Clifford Brown's or Charlie Parker's solos, and they get a sense of each of their personalities reflected throughout that musician's career. I get the same sense out of Cecil Taylor. I hate the official labels. They aren't as effective as just knowing there's a tradition from which the music comes, and it's really a matter of how each musician or group interprets the music they grew up with and how they turned it into their own music, from their own personalities and life experiences. And it reflects the time they were making their music.

AAJ: Who were some of those musicians who stimulated you personally?

SS: I was already playing trombone when I was ten years old, and I started listening to WRVR in New York and all the records that my father had. There was Vic Dickenson, Jack Teagarden, Kid Ory, all those early trombonists I loved very much. I listened to Tommy Dorsey, who was a very good improviser before he became a big band success. I loved the sound of the trombone. I listened to Jack Teagarden play "St. James Infirmary" a thousand times maybe, and I just loved it.

When I was around age 15, I first heard Roswell Rudd, and from there on in, I got interested in freer music. He just did something so very different, but he came from a tradition of New Orleans Dixieland music. He brought some of that tradition into the music he played with Archie Shepp and some of the freer musicians he played with in the 1960s and 1970s. So Roswell led me to Archie Shepp, and I got curiouser and curiouser, and discovered Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and all those whose recordings were available at my local department store in New Jersey.

AAJ: So who came along after that?

SS: Later, I got into Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, Glenn Spearman, Frank Wright, and so many musicians that I would gravitate towards emotionally and listening wise such as Evan Parker, George Lewis, and Ray Anderson. I've always been a pretty avid listener, and I'm always curious about what people are doing, especially new trombone players.

Pushing the Limits

AAJ: Having been a trombonist myself, your technique on that instrument seems to me to be incredible, one might almost say outlandish! How did you develop your exceptional technical repertoire?

SS: As I was choosing the path that I chose, I studied with Ed Herman, a trombone player from the New York Philharmonic. I got to study with Jimmy Knepper. I went to Jazzmobile a few times, and Curtis Fuller was the teacher there. Then I went to Jazz Interactions, and studied with Roswell Rudd. And sometimes Grachan Moncur III would substitute for him. When I practice, I do a lot of bebop phrases, using double and triple tonguing, and of course I go away from the chord structures and practice improvising that way just off of the melody. So I've acquired quite a wide range of both technical and creative input. But I think young musicians might get too hung up on the technical aspects and should focus more on the creative process.

AAJ: How would you describe your own creative process?

SS: For me, bebop is part of the language, and then I go and make different sounds with the instrument, maybe the way early Dixieland players did, playing along with recordings of a wide variety of musicians and then just trying things on my own. But I'm also listening to a lot of European and modern music as well as European improvisers like trombonists Paul Rutherford and Wolter Wierbos. I think all these influences inform what I'm doing now.

AAJ: So you stay open to new influences.

SS: Absolutely. There's a great interview with Miles Davis where Dick Cavett asked him, "What gets you going every day? What's important to you in life?" And Miles said, "Learning something new every day." The learning never stops. You can't know everything in one lifetime.

AAJ: My thoughts are going in a couple of directions, and one of them is about sound. I think that sound or sonority is very important in music. When I first heard Ornette Coleman, I was put off by his sound, his use of a plastic saxophone. Now, I'm beginning to understand why he did that and appreciate it more, but personally, I love a sound that's rich, full, like trombonist Urbie Green. But there are so many other sounds that are valuable in jazz. What are your thoughts about taking the sound to different places to make it meaningful in particular ways? I think of Don Cherry playing a pocket trumpet. All the different sounds that are possible. Jazz has contributed enormously to exploiting all the different sounds of the instruments.

SS: Well I think that sound is the basis of everything else in music. You have to give yourself over to your own sound, live in it, understand it and be close with it, absorb yourself in it and the sound of the group you are playing with. I remember reading that when John Coltrane joined Miles Davis, some of the critics said Trane had a "thin sound," and now we don't even think of that, we just think of Coltrane as a genius giant of the saxophone. They said he had a "smaller sound," but it was his unique sound, and he used it to great effect. Sound is everything

AAJ: I never thought that Trane had a smaller sound. That's not the way to describe it. It's not "fat" like, say Ben Webster and Coleman Hawkins, but it has a very rich timbre, and much like the human voice. Speaking of the sound of that era, the bebop players like Bird and Dizzy Gillespie sharpened the sound, omitted vibrato, made it very crisp.

SS: Right. I think that is what they meant, they were comparing Coltrane's sound to a Ben Webster and it was very different from what listeners were used to. And what you say about Bird and Dizzy got codified, sound-wise, technique-wise and that's mainstream jazz now.

AAJ: Earlier you said that last night, you and the group played "free improvisation?" What do you mean by that?

SS: We improvised an hour long set, no written music, no discussion about what we were going to do: myself on trombone, Michael Bisio on bass, and Gebhard Ullmann from Germany on tenor saxophone, who also played bass clarinet. No drums or piano. I've been partnering with Gebhard for twenty years.

AAJ: So there are no tunes, key signatures, or pre-determined harmony?

SS: No, not at all. Are you surprised? We do have what I would call a vocabulary each one of us delves into when we play together. We're not entirely in the dark about what we're doing!

AAJ: But you're just playing whatever comes to your mind, wherever you want to go?

"Spontaneous Compositions"

SS: Exactly. And by listening to each other we string together what many people now call "spontaneous compositions."

AAJ: OK, let's say I'm your average Joe. I'm sitting in the audience, and I'm thinking, "What the hell are these guys playing!!?? I'm open-minded enough to give it a chance. Could you say what you are trying to accomplish when you don't have this familiar structure to work with?

SS: Well, to begin with, we're not thinking of those things. We're just trusting all the experiences musically and in life that we've had up to that point, and we're responding to each other in a sensitive way. Whether that sensitivity is raw or quiet, or whatever volume or emotion it is, we're responding to each other. Maybe one of us starts to play something and then I'll respond to it, and then -the main thing that we were just talking about -is the sound. And we're also taking into consideration the space itself. The sound of the space. The space in Kingston had very live acoustics, so I discovered that the softer I played, I could find some ideas that were more fragile and kind of deep, maybe sad in spots. And then we got pretty raucous at times! But I found with those live acoustics that I didn't have to play very loud to get a lot of emotion across. The space and audience are actually part of the band and the music.

A Comparison with Jackson Pollock's Art

SS: If you're an audience member who is confronted with this sort of playing, and say the music was entirely new to you, I'd suggest doing what I do when I'm exposed to a new kind of music. I close my eyes, and I just listen and let it take me from there. It's a bit like looking at a Jackson Pollock painting for the first time. He's dripped some paint in one part of the canvas, and then does something else in another place. It seems random, but then when you look at it for a while, it becomes meaningful and alive for you, as it has for so many art lovers.

With music, it's not all drips, you can hear some kind of melody, chords. It's very important to hear where it starts. You wait for the moment of the first sounds, and then you're ready to take the train on the journey with the musicians. Maybe stepping back and listening to the whole "picture" you might gravitate towards a specific sound or musicians and focus in on that. Many times listening back to something I did or listening to someone elses music I got turned on by a specific sound and don't recognize it then I go looking for its source. Where is that sound coming from? Who is making it? is the source two or more musicians making it? That's what I love about this music, discovering a unique sound or interplay of sound that is happening spontaneously.

AAJ: So that journey has something to do with the collective experiences of musicians and listeners. It's got some kind of structure underlying it. It's not total chaos. Like with Jackson Pollock, you begin to see how organized it is beneath the apparently random drips of paint.

SS: Of course! As raw as they may be to some, his paintings are beautiful. And the same thing can happen with a group of musicians with sounds. They're listening very hard to what they're contributing at each moment. And what you'll find is that a freely improvised performance will go through many different permutations. The musicians know how to move between the parts or movements to develop their ideas. So if you listen carefully, and with an open mind, you're going to have a very rich and rewarding musical experience. But you do have to overcome any prejudice that you have. You just have to follow along and see what you might be drawn into, just as you would with a new work of art of any kind. And with recordings, you have a chance to go back and listen again to see what else pops up. I discover new things each time I listen to one of them.

AAJ: Jazz is different from paintings, in that jazz takes place in time and can never be repeated, while a painting is "frozen" in time. It takes place in space rather than time.

SS: Yes, but you can think of jazz as a kind of "action painting," where you watch the artist or artists going through his or her process. Its fascinating for me to see, hear, be involved in that as a musician and/or listener. In fact, there's quite a bit of combined music and visual arts being done today. Jeff Schlanger creates paintings in response to the music as it's played. Another artist in New York, Bill Mazza, does computer generated colors and lines while the music is taking place.

AAJ: It seems that jazz has really entered the multi-media age.

SS: Maybe, but that's not my point. I was just making a comparison between visual art and music. For me, it's more than enough to focus on the music and how I'm relating to it. Listening with your eyes closed is sometimes very rewarding: let the music paint the picture for you. That is called "acousmatic" listening, sound one hears without seeing the originating cause, which we all do in some form or another.

AAJ: How can someone tell whether music that's very experimental or lacks conventional structure is likely to be meaningful and important as opposed to a gimmick cleverly designed to get attention?

SS: That's an interesting point. Great musicians can play junk, whether they play the same old familiar stuff to please their fan base and make some money or just play nonsense. I think the primary objective of jazz improvisation is to play something new that hasn't been built before sound-wise and spark something in people that they wouldn't get any place else. To inspire them, even heal them. I think it also has to do with a musician's personal makeup and depth as an individual. What it means to them to be doing this in the first place. It's a good thing for musicians to think about that. Why are you motivated to be working in this art form?

AAJ: But sometimes it takes a lot of time before history decides whether the music is significant or not. Time will tell what the music means for the total context.

SS: That's true, in terms of the big picture. But most musicians aren't thinking that way. They really think about what they are doing when the concert starts musically or maybe their next gig or recording and what they're contributing to it. Thinking about the big picture prevents you from just being yourself. But your point about history is correct. You never know what might later turn out to be of great importance. And, on a more personal level, you never know when your music is going to have a positive effect on some listener who is depressed or lost a partner, or is going through some other personal problem, and your music lifts them up just a little bit, maybe years later, by way of recordings, and maybe that's the real value or purpose of why you played it! You can touch someone you don't know when you least expect it.

From Modernism to Post-Modernism in Jazz

AAJ: Returning to our original topic of the scope of jazz today, I for one am old fashioned-and I think there are many from my generation who are like me. I came of age in the 1950s-60s. The prevailing philosophies were existentialism and modernism, which allowed that there were truth and beauty amid the turmoil and absurdity of life. Then, everything about truth and beauty seemed to fall apart. The true and the beautiful were, as Derrida said, "deconstructed." So we went into the era of "post-modernism,' in which truth and beauty can be whatever we want it to be. "It is what it is." An architect can make a very modern building and put a Roman column or a couple of medieval gargoyles at the entrance. Anything goes. Can we say that a lot of the new music is "post-modern?"

SS: Maybe, maybe not. I think your problem may be that you're living in the time you're in, and you're trying to define it at the same time. It's very hard to do that. And you're talking about relativism versus universal truth. In terms of music history, the baroque era of J.S. Bach wasn't really defined as "baroque" until the 1950s, when musicologists gave it that name. Bach didn't know he was composing baroque music! We don't really know what the music of today is all about either.

With jazz, we have historical periods that we retrospectively call Dixieland, swing, bebop, but we don't know what we're in today. All we can say is that musicians are drawing on the whole tradition of jazz and other music from around the world. It's all wide open for everyone to use. But we don't yet know how it all comes together or how history will view it.

Ethnic and Geographical Diversity

AAJ: If we could view jazz today from a wide perspective, from a space satellite, so to speak, we would see that it has disseminated around the world -no longer just America and Europe -it's finding a significant place in Asia, Africa, South America, Australia, you name it. We would also see that we have many different forms and influences from everywhere and of all kinds. In one respect, that's very enriching and stimulating and creative, but if I were a musician today, I would feel perplexed. I wouldn't know what to hold onto.

SS: That's a very good point. There's so much out there now, and it's all available at your fingertips on the web, and so many diverse influences. It's very hard to know where the center is, what's the foundation. For musicians coming up today, that could pose quite a dilemma. That could have a numbing effect as I mentioned earlier, not knowing what direction to go in. And to deal with it, too many of them latch on to the "jazz canon" that they learn in school, and they stick with it because it's a safe area, but that could stifle their creativity and finding their own voice. It's a real problem.

For Young Musicians Seeking Their Own Way

AAJ: So what guidance could you offer those young musicians?

SS: I'd say keep your ears open to whatever comes your way. But also get together with the musicians who live and work in your neck of the woods. There, you can create your own vocabulary and your own music. Don't sit at the computer or stereo. Get out and play with the musicians you know!

AAJ: And that way, you'll be developing your own vocabulary.

SS: Absolutely! That's the primary directive of what an artist should do.

AAJ: Bobby Zankel made a similar point. Rather than try to fit in with the whole jazz scene today, he's focusing on his own bands and working on his own path and vocabulary.

SS: Yes, it's so important to find your own path and stay with it.

AAJ: Bobby also said that when he started out, he tried to play as much as possible in bands with more experienced musicians so he could learn from them.

SS: Yes, and even now I try to get with the guys who influenced me and see what else I can learn from them.

AAJ: So maybe what we're saying is that mentorship is essential.

SS: It doesn't necessarily have to be a formal mentor relationship. Just hanging out and exposing yourself to someone you admire and appreciate, talking to them, you're going to absorb a lot just being around them.

AAJ: To wrap up our conversation, what's the message you'd like readers to take with them?

SS: I would say, whether you're a fan or a musician, go to hear live music more. Check out venues and musicians who are new to you. Expose yourself to new music. Go with an open mind and listen to what the music is all about. Think of it as listening to a painting. It's a great way to get away from your daily preoccupations and just let the music overtake you. You may discover a solution to a particular problem in your personal life or work life while listening to live music. It's important for all of us, musicians or not, to stay open to new experiences. That's what makes life worthwhile and fulfilling.

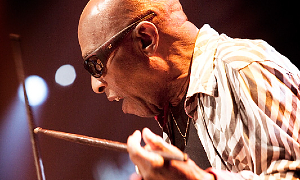

Photo Credit: Ziga Koritnik

Tags

Interview

Steve Swell

Victor L. Schermer

Roswell Rudd

Grachan Moncur III

Cecil Taylor

Ornette Coleman

David Murray

Anthony Braxton

Roscoe Mitchell

Wadada Leo Smith

Henry Threadgill

Clifford Brown

Charlie Parker

Vic Dickenson

Jack Teagarden

Kid Ory

Tommy Dorsey

Jack Teagarden

archie shepp

Albert Ayler

Glenn Spearman

Frank Wright

evan parker

George Lewis

Ray Anderson

Jimmy Knepper

Curtis Fuller

Paul Rutherford

Wolter Wierbos

Miles Davis

Urbie Green

Don Cherry

John Coltrane

Dizzy Gillespie

ben webster

Michael Bisio

Gebhard Ullmann

Comments

PREVIOUS / NEXT

Support All About Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who make it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.